![]()

BY BETH ALLEN

BY BETH ALLEN

September 1997

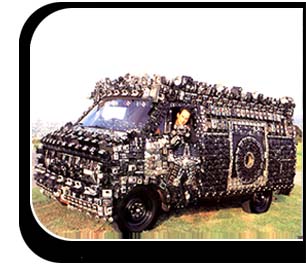

When I arrive at Harrod Blank’s house in Berkeley, he is outside messing around with his Camera Van, caulking gun in hand. The van, a 1972 Dodge covered with more than 1,700 cameras, is a mind-blowing moving multimedia sculpture that documents the reactions of those it passes. The one working still camera, mounted below a working video camera wired to a monitor inside on the dash, is the most expensive camera on the van, and it’s hidden beneath cheap, clunky automatics to protect it from being stolen. After an elaborate film-loading ritual, as well as some monitor-tinkering and battery-fiddling, we are ready to go for a ride.

As we take off, Blank cranks up an inside stereo (reggae) and an outside stereo (Hawaiian tunes), and gets his C.B. (which has P.A. speakers mounted outside) in hand. “Good evening. Say ‘cheese’ !” Blank’s voice booms out at passing bicyclists, people walking dogs, strolling couples. Meanwhile his hand constantly pushes buttons on the dash that control the camera, capturing amused smiles, stares, and looks of surprise. We cruise down Telegraph Avenue, and I laugh as I notice all the cameras being whipped out to take pictures of us. “Oh yeah,” Blank says. “This is a camera magnet!” After a while he reminds me, “I don’t know any of these people, by the way, that are waving and stuff. I have no idea who they are.” But most likely more than a few know who he is.

For more than 10 years Blank’s life has revolved around one thing — art cars. An art-car Renaissance man, his 1992 documentary film Wild Wheels and the assorted art-car projects he has been absorbed in — his two art cars, caravans, photographs, calendars, a Wild Wheels book, postcards, lectures, even refrigerator magnets — have made him an unofficial spokesperson for a burgeoning movement.

“I’m a jack-of-all-trades in a lot of ways,” Blank says. “When people ask me what I do and what I would classify myself as, I don’t know what to say. I’m a self-made entrepreneur with a self-made career that I just kind of fell into.”

His first art car, an elaborately decorated VW bug, aptly named Oh My God! after what people exclaimed upon seeing it, led him into the world of wild wheels. Seeing Oh My God! — with its bones, trophies, toys, and whirling plastic sunflowers, its globe hood ornament, the rooster and Rasta paintings on its doors, and the television mounted on its roof — people would often tell him about other art cars they had seen in other states. Blank began visiting and filming these artists and their cars, documenting the subculture he was stumbling on. In 1988 he attended his first Houston Art Car Parade, an annual event that brings together art cars from all over the country.

By then, Blank had seen and heard of all kinds of cars — cars covered with buttons, priceless jewels, beads, dolls, marbles, bones, kitchen faucets, crosses, mirrors, city landscapes, autographs, plastic fruit, lights, shoes, stained glass, postcards, and live grass. Covered with simple painted stencils or silicone-caulked with objects, transformed with eye-catching paint jobs or elaborately welded creations, art cars were out there — but they were scattered across the continent. Meeting the Houston parade organizers was a turning point in Blank’s life, as well as theirs.

“Funny thing is, we helped each other a lot,” Blank says. “I had all these contacts that I turned on to the parade, and they turned me on to some more for the movie. The movie helped promote the parade, and the parade helped promote the movie, and those are really the two forces behind the so-called movement.”

With Houston’s Art Car Parade and related events having gone on for a decade, I ask Blank why he was the first to bring this subculture to the public eye. “Because no one has focused their energy, their time like this as long as I have,” he says. “I could be considered a professor. I’ve got a Ph.D. in car art!”

But Blank’s Ph.D. offers no promise of a secure future. Although according to Blank’s estimate Wild Wheels has been seen by 40 million people around the world (it has even been a national PBS special) and translated into more than 20 languages, Blank hasn’t seen much money for it. His other projects also struggle along, and he still considers himself a sort of “gypsy,” living on the edge, just getting by. Publisher interest in his Wild Wheels calendars has been inconsistent: it was dropped after one year in 1991, picked up again in 1994, only to be dropped and picked up again.

He told me that the Surface Transportation Policy Project had agreed to publish the calendar in 1998. He can’t believe it.

“Do you know how big that is? It’s like, these are people who are saying they want art cars to help challenge transportation in this country, take transportation to another level.” He fantasizes that they will finance converting the Camera Van from gas to electric and sponsor it as an alternative mode of transportation. It’s just one of his many fantasies about sponsors. He has already written the big camera and film companies — Kodak, Canon, Fuji — all of whom sent him rejection letters telling him they weren’t interested, but to “keep [them] informed of future projects.” The local camera shop Adolph Gasser is among his few supporters. He has used his van to promote the store, and Gasser has donated to his cause.

He told me of one offer he almost got: “I got invited to go to Japan by a Japanese political candidate this year. He wanted me to come so he could ride around in the van and get ’Generation X’ voters. I don’t know much about politics, but I liked the idea of going to Japan! They said they’d ship the van, pay all the expenses, no problem. Then they wrote me back a few weeks later that there was no way I could come because the vehicle codes in Japan would not allow me to drive the van. They couldn’t allow me to drive it but could tow it from city to city. The candidate didn’t want to ride in a van that was being towed. And I don’t blame him.”

I expressed surprise that no one had jumped at the chance to put his amazing wheels in commercials or to publish a book with pictures taken by the Camera Van. He is surprised too. “I can’t believe it either ’cause when you see the pictures, I think they’re incredible and I just don’t understand why all these people I’ve written to don’t get excited. It’s like, this is a whole new form of photography. You can’t do this without a camera van.”

Snapshots of surprise

When I attended the Houston art-car parade in April 1997, I had a chance to see some of Blank’s Camera Van pictures during a slide show he presented. Most were from a road trip he and his girlfriend took from the Bay Area to New York. The funniest of these were successive shots of individuals reacting to the van. One shot would capture an unsuspecting stare from a person who, after the first flash, would then automatically smile and pose for a second shot. My favorite photo was one of a backwoods farmer, standing alone framed only by a huge blue sky and an endless field, a look of utter confusion on his face. “He thought it was a spaceship,” Blank remembers, chuckling.

For Blank, the photos are really what it’s all about, something he’d always wanted to do but didn’t know how. “You see, for years I’ve been trying to take pictures of people reacting to Oh My God! but I couldn’t get the pictures. I tried for years to justify to other people why I do this, because they thought I was crazy. I was hoping to show them pictures of people’s reactions and, you know, I couldn’t get them.”

The answer to his dilemma — an expensive one — was the Camera Van. Although he bought the van for $400, he has spent by his estimate tens of thousands of dollars keeping it running. I ask him exactly how much. “I don’t even know, but I know it’s a lot. I purposely don’t want to know, because it’s so much money. I would never in my right mind justify spending that much money on an object, a car; there’s no way, I would never do it.”

He spent a year collecting donated cameras and another year siliconing them on with help from friends. He wired the entire vehicle himself — C.B., P.A. system with outside speakers, video monitor, two stereos, and a slide projector with which he shows slides of the van’s creation and pictures it has taken. Sighing, Blank fantasizes yet again: “I’m not to the level I want to be at. If you could imagine this thing with working cameras all the way around it, it would be great.”

But more than one functioning camera is a frill he can’t afford just yet. Keeping the van running is already a feat. “I just spend the money because it has to be spent to make this thing happen. I don’t even question it; I just do it. Same thing with the film.”

The film in question is Wild Wheels II, a work in progress. Like Wild Wheels, it will document art-car artists and their wheels, but it will delve into their lives a bit more. But Blank is strapped financially, and like his elaborating on the Camera Van, the film will have to wait. In the meantime, the National Geographic TV show has commissioned him to do a shorter version, which he has titled Driving the Dream.

Later, back at his modest home (actually a small house behind his father’s), he shows me the rough cut. I love it. In it we meet Harry Sperl, who collects anything and everything that has to do with hamburgers. His house is full of them; even his bed is a giant hamburger. He rides a moto-trike that has been specially molded into — what else? — a hamburger. Gene Pool, creator of many “grassmobiles,” which have live grass growing on them, tells us about his semidisastrous project to create a grass-covered bus as promotion for the St. Louis Cardinals. Former racecar driver Hyler Bracey shares his horn-covered truck, with which he can conduct a blaring riverboat-motorcycle-steam tractor-firetruck honking orchestra while driving.

As of now the film is 26 minutes, all that National Geographic is willing to pay for. Better than nothing, Blank thinks. “The worst thing is that they get the rights for two and a half years. But I couldn’t get the money to make it, so at least it will get out there.”

There are various other projects Blank is helping with at the moment as well. “The caravan movie, Art Car Caravan 1995 — The Movie, is another one. It’s a video and I’m producing and directing that one, too. It’s fun; it’s the experience of being in a caravan, which is so killer.”

Both Art Car Caravan and Driving the Dream will premiere at the first annual ArtCar WestFest, taking place here in San Francisco at the end of this month. The festival will be an indoor and outdoor exhibition of art cars and art produced by their owners. “I decided I was tired of going to Houston every year. Why not do something here?” Blank says. Blank found enthusiasm and help from Philo Northrup, another local art-car artist (creator of Truck ’N Flux). Together they are curating the three-day event of art cars, art-car photos, live music and performances, a fashion show (featuring clothing by San Francisco’s Space Cowgirls), beer from Twenty Tank Brewery, and activities for all ages. It will be the largest event of its kind on the West Coast, with more than 50 art cars from around the country on exhibit, including Ripper the Friendly Shark, High Heeled Shoe Car, Jesus Chrysler, Doll Car, Cowasaki (an art motorcycle), Buddhist Temple Mobile, and, of course, Oh My God! and the Camera Van.

Cars are sacred

“I’ve been trying to figure out what exactly makes us [car artists] do this,” Blank says. “My girlfriend was saying, ’It’s just for the attention,’ and I said, ’No, it’s not just getting attention. It’s the same thing as music or writing or performance; it’s a totally new medium of art.’ The definition or the status of an automobile in our society is so prevalent that people don’t feel they have the freedom to do it; they don’t feel that it’s OK. [Cars are] like a sacred thing; to take a car and put shit on it is sacrilege. Most Americans would never think to put anything on their car.”

But things are changing, slowly, Blank tells me as he sits quietly in the Camera Van, which he has parked for a while to cut down on distractions. He believes that the art-car movement is part of a larger search for creative outlets in our society.

“The funny thing is that something is going on that’s way beyond car art, way beyond Burning Man, way beyond UFOs, way beyond bisexuality, way beyond all these current trends of reaching out for more. I think people as a whole are becoming dissatisfied with the rituals that we have, like football games and churches and life in general. Work to pay the rent is not enough anymore. People want to go further, in their soul and life, and I think that’s what all these things mean.”

As we wrap up the interview I look up and notice a car rushing past us shaped like a giant potato, with “SPUD” in big letters on the side. Excitedly, I bounce in my seat and point it out to Blank, who, having seen it before, is unfazed. “It promotes a potato business,” he tells me. And smiles.

How to make your own wheels wild

From an eyesore to a masterpiece — if you have the canvas, the urge, and the sweat and time to put into it, your very own wild wheels could be just weekends away. Harrod Blank offers some tips for art-car virgins so you don’t have to learn the hard way:

Painting: One Shot, an oil-based enamel paint used by sign painters, paints over anything and stays on. Oil-based enamels are the best (and the most toxic, so be careful). You don’t have to sand or prime. Apply with a roller for a nice even coat. One Shot holds its color well and won’t splotch and fade like spray paint.

Sticking things on: 100 percent silicone is available at any hardware store. It comes in a tube and is used with a caulking gun.

Sticking heavy or really big things on: Use self-tapping head sheet metal screws and plumbers tape (flexible metal tape that has holes in it) to attach larger items. You can use a drill to drive the screws right into your car, but remember, the screws have to be self-tapping.

Making shapes: If you’re going to sculpt something, use chicken wire and foam to build a base.

Insurance: Don’t ask, don’t tell. Some wild wheels could be seen as a liability. Get your car insured prior to decking it out.